by Vanessa Potter

As I started to wake, and sleep loosened its grip on me I stretched out my body feeling the warmth of the morning sun caress my face. A heartbeat later the crushing reality of where I was hit me like a high-speed train. I was not at home lying within the safety net of my family, opening my eyes to see my small son wriggling his way into bed with me. I was in hospital. And I was blind.

In 2012 I was a successful tv producer making commercials for well known brands. Like many women of my era, I was juggling a demanding job, two small children and a husband with an arduous daily commute of his own. I was shouldering much of our family life, and it had taken its toll. In the summer of that year I decided to take a break. I had just spent a relaxing summer with the children, and was about to return to work when fate stopped me in my tracks.

I thought I was resourceful, organised – and to a point I am, but not even the most capable producer can forecast the future. Nothing could have prepared me for waking up one morning to find myself blind and paralysed. It was like I had been sucked into a black hole – a gaping abyss where I could not see or feel the world around me. The darkness was suffocating, and the numbness that had coursed its way through my feet and hands had left me unable to stand unaided or use my hands. Terror squeezed my ribs, making it hard to breathe and my mind spun trying to comprehend what was going on. Two of my major senses had just been wiped out in the space of a few days, and the worst of it was that nobody knew why.

I thought I might never recover, but slowly my sight began to re-emerge. Staring across my hospital room a week later, I sensed that the blackness was perhaps just a little less black. I wondered if there was a lighter patch to my right, and perhaps there was a pale shape hovering over my bed. As I stared hard for long minutes I suddenly realised I was looking at my own pillow. The elation that flooded through my body at that moment was galvanising, and left me determined to do whatever I needed to do in order to make myself see again.

I thought I might never recover, but slowly my sight began to re-emerge. Staring across my hospital room a week later, I sensed that the blackness was perhaps just a little less black. I wondered if there was a lighter patch to my right, and perhaps there was a pale shape hovering over my bed. As I stared hard for long minutes I suddenly realised I was looking at my own pillow. The elation that flooded through my body at that moment was galvanising, and left me determined to do whatever I needed to do in order to make myself see again.

That mindset changed the direction of my recovery. I suddenly realised that I did in fact have resources in place; in fact I had lots of them. Without having thought about it I was using breathing techniques to lessen the tightness I felt in my chest, and to counter the anxiety that at times ploughed through my body. Focusing my attention on my breath gave me some mental distance, and seemed to somehow separate me from the maelstrom inside my head. Taking slow breaths in and counting the breaths back out again I calmed my mind and my body simultaneously. What was perhaps a little strange was that I did these things without any conscious effort – without thinking about it. I was simply nurturing myself in the only way I knew, by using the one thing I had left available to me at the time – my mind. It’s easy now to recognise this as mindfulness, but in fact back then it was simply survival. My body responded to my trauma in an innate and compassionate way, gently whispering to me what I needed to do.

It is well documented that the breath is an integral part of a mindfulness meditation practise, but do we know why? At some stage during my recovery my fear was replaced by a deep curiosity to understand these primal responses. I learnt that the breath is a complex and multi-part process. What I hadn’t known at the time was that breathing could trigger change, and help me balance my nervous system when I felt out of control. When we breath out slowly messages are sent to the brain, which stimulate the parasympathetic part of our nervous system. Breathing is in fact like a herd of horses. Once you start it off, it cascades and triggers other more nurturing responses – in turn having a calming effect upon the body. My meditative breathing did just that. Whilst a mindful practise is not necessarily intended as a relaxation tool, this is often a side effect of taking time to focus on our breath in this way.

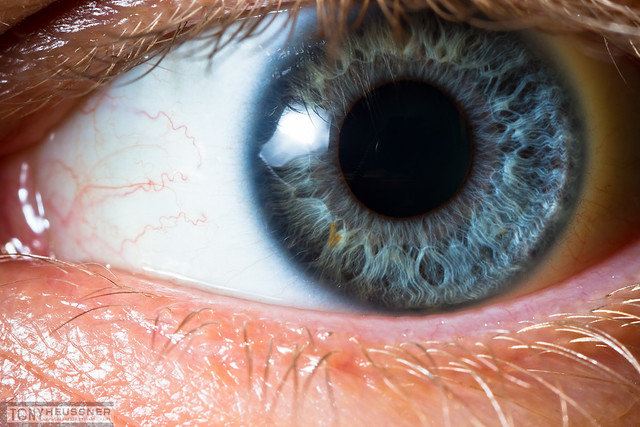

As my sight slowly returned layer by layer, I documented each strange visual twist and turn. Initially I opened my eyes to a flat monochromatic landscape with no faces or detail. Over time I would experience jiggling lines dominating my view. As I investigated the science behind my vision I learnt that in fact this was my own visual system coming back online, and reconstructing the boundaries of my visual world. I learnt that as colour began to return my sensory system got confused and mixed up these neural messages. I saw exploding colours which fizzed and sparkled, and my desire to understand this only intensified. My inquisitiveness didn’t end there either. Standing back and examining my coping mechanisms I was fascinated to understand how what I could only describe as my ‘acute awareness’ of my surroundings might have affected my recovery. As the weeks passed I would spend hours standing staring at roadsigns, kerbs and lamp posts in the streets where I lived. Breathing in quietly I would let my entire sensory army absorb whatever information it could. I became aware of lesser sensory channels, of sensing some small detail, rather than physically seeing it. I wanted to know what this kind of ‘seeing’ was, and why it seemed to stimulate my recovery. Working with a vision scientist at Cambridge University and a psychologist who has a Phd in mindfulness research, we worked our way through all that I had experienced. What we discovered was to change my view of life completely. In fact, my quiet way of seeing could easily be explained as mindful seeing. I was standing back from myself – from my expectations of sight and from labelling my environment. In fact I could not easily label my environment as I could not see it, so I had to accept it as it was. This way I became open to the many non-visual routes to the brain, and to a new, deeper way of perceiving information. I was paying attention to what was in front and around me with a different attitude, one of curiosity and patience. We don’t often stop and look, we just skim our surroundings, allowing our brains to prune the information we unconsciously deem unimportant. However, it was these missed details, these insignificant specs of light on the horizon that helped fill in my visual world. Without realising it I was helping my brain re-learn how to see, reminding it what edges were, how they linked up and demarcate our landscape – I was noticing all of the fragments of life that we normally skim over and relishing each and every tiny particle. I was reminding my brain of the ‘rules of seeing’ and gently allowing my visual system valuable time to just – see.

As my sight slowly returned layer by layer, I documented each strange visual twist and turn. Initially I opened my eyes to a flat monochromatic landscape with no faces or detail. Over time I would experience jiggling lines dominating my view. As I investigated the science behind my vision I learnt that in fact this was my own visual system coming back online, and reconstructing the boundaries of my visual world. I learnt that as colour began to return my sensory system got confused and mixed up these neural messages. I saw exploding colours which fizzed and sparkled, and my desire to understand this only intensified. My inquisitiveness didn’t end there either. Standing back and examining my coping mechanisms I was fascinated to understand how what I could only describe as my ‘acute awareness’ of my surroundings might have affected my recovery. As the weeks passed I would spend hours standing staring at roadsigns, kerbs and lamp posts in the streets where I lived. Breathing in quietly I would let my entire sensory army absorb whatever information it could. I became aware of lesser sensory channels, of sensing some small detail, rather than physically seeing it. I wanted to know what this kind of ‘seeing’ was, and why it seemed to stimulate my recovery. Working with a vision scientist at Cambridge University and a psychologist who has a Phd in mindfulness research, we worked our way through all that I had experienced. What we discovered was to change my view of life completely. In fact, my quiet way of seeing could easily be explained as mindful seeing. I was standing back from myself – from my expectations of sight and from labelling my environment. In fact I could not easily label my environment as I could not see it, so I had to accept it as it was. This way I became open to the many non-visual routes to the brain, and to a new, deeper way of perceiving information. I was paying attention to what was in front and around me with a different attitude, one of curiosity and patience. We don’t often stop and look, we just skim our surroundings, allowing our brains to prune the information we unconsciously deem unimportant. However, it was these missed details, these insignificant specs of light on the horizon that helped fill in my visual world. Without realising it I was helping my brain re-learn how to see, reminding it what edges were, how they linked up and demarcate our landscape – I was noticing all of the fragments of life that we normally skim over and relishing each and every tiny particle. I was reminding my brain of the ‘rules of seeing’ and gently allowing my visual system valuable time to just – see.

Understanding that I had inadvertently developed a regular mindfulness practise was fascinating to me, and helped me understand the origins of this way of life, for indeed I do see it as a way of life – a way of noticing life. I now meditate regularly, and this is as interwoven into my life as brushing my teeth. I don’t really see it as a formal practise, although I do take time out to meditate, but the act of mindfully acknowledging my life is a switch I flick on constantly throughout my day.

My sight loss was a pivotal moment in my life, but I was, and still am, amazed at the capability and creativity of our bodies and minds. When the doctors didn’t know what was wrong with me, or what to do – my own body did, and for that I will always be grateful.

Enter PATIENT at the checkout on Bloomsbury.com to receive 30% off Patient H69: The Story of my Second Sight by Vanessa Potter.

VANESSA POTTER

@patienth69

Latest posts by Admin (see all)

- Poetry as Mindfulness - January 15, 2021

- How Mindfulness Stopped Me From Over-thinking My Life - December 12, 2020

- Give The Gift Of Compassion This Holiday Season With Co-Mindfulness - December 7, 2020